7CO01 Assignment Example

- February 2, 2022

- Posted by: Assignment Help Gurus

- Category: CIPD CIPD Level 7 HUMAN RESOURCE

7C001 Work and Working Lives in a Changing Business Environment

7C001 Work and Working Lives in a Changing Business Environment

Level 7 Advanced Diploma in

- Strategic People Management

-

Strategic Learning and Development 7CO01 Work and working lives in a changing business environment

Question 4 750 Words

What are the main causes of increased social inequality around the world? To what extent could changes in HR practice help to reduce social inequality? Provide examples to support your answer.

Question 8 750 Words

Explain how the management of people tends to vary depending on whether a labour market is tight or loose. Illustrate your answer with examples from your own observations and your reading.

Question 12 750 Words

Identify THREE distinct steps that managers can take to encourage greater innovation and creativity in their organisations. Which do you think would be most effective in your sector or industry? Justify your answer.

Question 15 750 Words

You have been asked to make recommendations to your senior management team about how your organisation might improve its record in the area of sustainability. You are asked to identify TWO distinct interventions that will not be too expensive to implement. What would you recommend and why?

SOLUTIONS

7C001 ASSIGNMENT ANSWERS

SOLUTIONS : TASK 1

Challenges faced in managing an aging workforce

We are living at a time when people live longer and are healthier and as such want to work for longer. This demographic trend necessitates organisations to plan for an ageing workforce and their eventual exit of the company as well as creating a conducive environment for them to continue being productive. Indeed, workforce statistics reveal that an ageing workforce is an emerging trend across the globe for example it is estimated that in the US 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 years on a daily basis which is traced back from 2011 and is expected to continue up to 2030 (Verlinden, 20218). In the UK it was reported that by 2022 there will be 700,000 less people within the age bracket of 16 to 49 while there will be 3.7 million people aged between 50 and the state pension age (Roper, 2016). This then mean that people professionals in public and private organisations have a daunting role of managing different generations at the workplace.

In reference to a rise in an aging workforce, one of the challenges that has been recognised through research and confirmed by people professionals who have had extensive experience in practice is bias. Segal (2019) astutely stated that older workers are highly qualified and possess priceless tacit knowledge nonetheless conscious and unconscious bias affect how they are treated at the workplace. Similarly Roper (2016) argued that unconscious bias is rampant in organisations as there is a prevalent social and national perception that people in their late 50s are on a downhill trend and thus the tendency for such professionals to be lumped in a box regardless of skills and characteristics. Bias in reference to age is enshrined in organisational policies and practices such as tendency to overlook training and development needs for aged employees. This was confirmed by a 2014 CIPD report that found out that 22% of organisation had no provisions ensuring that all employees irrespective of age had access to training and development. Bias is also manifested through stereotypes such as the old being regarded as rigid, they are too slow and tend to have more sick days (Verlinden, 2018). It is also manifested in reward and remuneration strategies where organisation get rid of staff in their 60s citing their high perks gained over time as well as in recruitment practices as less employees above the age of 50 are recruited by organisations.

The second challenge experienced in the management of an ageing workforce is absenteeism. Verlinden (2018) presented absenteeism as an aging workforce trend that is attributed to several factors including health complications that arise with advancement in age. Hope (2017) cited a Centre for Economic and Business Research (CEBR) study that found that workplace absenteeism cost the UK an astounding £18 billion annually. This is further accentuated by the finding that a workforce with more than average number of older people often record absences that stretch over a prolonged period of time (Hope, 2017). From a business perspective, absenteeism amounts to loss in revenues nonetheless there are rising calls for business to embrace diversity and accommodating an aging workforce is a means to this call. This is also bolstered by arguments that age-diverse work teams result in increased productivity and performance though not backed up by empirical evidence (Weiss, 2009). Patterson (2018) argued that given that the demographics show that there will be a rise in the aging workforce people professionals can plan for it as aging comes with predictable impacts such as diminishing physical flexibility, hearing loss, reduced strength and other age related limitations. As such, the challenge of absenteeism should not be surprising to people professionals rather their biggest task should be how to effectively manage while still benefiting from the benefits of diversity and inclusion.

Recommendations for the aging workforce

Giving reference to bias on the basis of age, organisations can reduce the bias in policy by having an organisational policy audit conducted by a third party to identify policies and procedures that are age biased. The findings of the audit can then be used to reframe and alienate the bias.

Secondly, organisations should organise for trainings targeting all employees in a bid to make them understand age-based differences and how to harmoniously co-exist in a workplace context as well as harness the intergenerational wisdom in improving organisational performance. The training should also enlighten on how unhelpful stereotyping can defy and misrepresent generational categorisation. In addition training and development opportunities within organisations should be evenly spread within the different generations working in a company.

Segal (2019) recommended that in recruitment and selection exercises that are targeted as well as using blind screening in order to overcome the challenge of unconscious bias. This can proceed by having potential candidates omitting the demographic data when applying for vacant positions. Additionally, the aspect of salary should be scrapped as a way of mitigating unconscious bias against older workers.

In reference to absenteeism in an aging workforce, it can be mitigated by offering flexible working hours to allow for health related appointments to hospital. This can allow older employee to be more open and honest about their health and thus allow people professionals to adjust their duties and responsibilities accordingly. This can go a long way in ensuring that there no gaps in delivery of critical services within the company.

Flexibility can also be tailored in reference unpaid leave taking cognizance of the fact that older employees have fewer financial burdens. This can allow the older workforce to take a health break without making the company cater for absence related costs.

HR professionals can also manage absenteeism in the older workforce through training focusing on diversification of roles and responsibilities in alignment to changes experienced as you age. To this end companies can provide options such as ensuring that the workplace facilities are accessible, allowing older workforce to have a personal attendant at work, embracing ergonomics and adaptive equipment at the workplace such as providing foot supports and changing height of monitors as well as allowing assistive devices to minimise on the physical activities (Patterson, 2018).

Bibliography

Hope, D. (2017). Sickness absence: plan now for the ageing workforce. [online] Personnel Today. Available at: https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/sickness-absence-plan-now-for-the-ageing-workforce/.

Patterson, T. (2018). Absence Matters: Managing an Aging Workforce. [online] Disability Management Employer Coalition (DMEC). Available at: http://dmec.org/2018/09/14/absence-matters-managing-an-aging-workforce/ [Accessed 8 Apr. 2022].

Roper, J. (2016). HR Magazine – The HR challenges of an ageing workforce. [online] HR Magazine. Available at: https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/content/features/the-hr-challenges-of-an-ageing-workforce.

Segal, J.A. (2019). Reducing Age Bias. [online] SHRM. Available at: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/all-things-work/pages/reducing-age-bias.aspx.

Verlinden, N. (2018). Aging workforce challenges: Trends, Statistics and Impact. [online] AIHR. Available at: https://www.aihr.com/blog/aging-workforce-challenges/.

Weiss, M. (2009). Absenteeism in Age-Diverse Work Teams. Labour Markets and Demographic Change, pp.40–57.

SOLUTIONS : TASK 2

The Covid19 pandemic significantly affected life in general, from the way we interact at a personal level to the way organisations and the world operate. When its end was not forthcoming human beings and indeed organisations reacted by finding new strategies to survive and operate. In respect to the labour market system, employers reacted by implementing several changes including freezing recruitment, initiating wage flexibility measures, redundancies, furloughing of staff and homeworking (Cipd, 2020). As the pandemic measures initiated by governments across the world wane off there is growing appreciation that post Covid19 business as usual will not resume across organisations (Cipd, 2020).

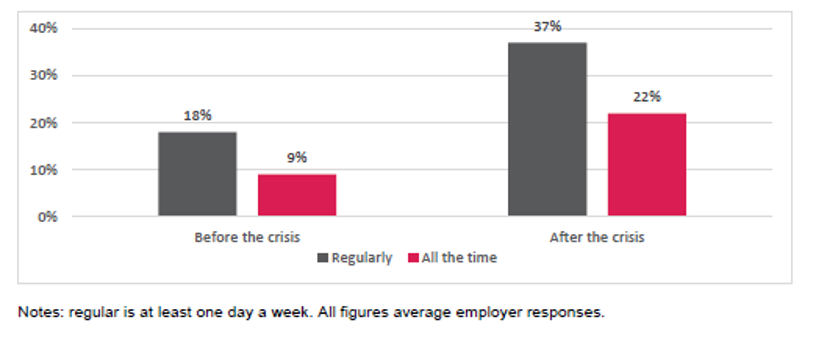

To a large extent, I agree with this assertion and prediction as some changes initiated in the working world had been on considered pre-Covid19. For example, working from home had been considered in the quest to improve on employee wellbeing. Basing on the Cipd study titled Embedding new ways of working: implications for the post pandemic workplace the biggest long term impact of the pandemic will be the shift towards working from home. The survey data informing the study indicated that pre-Covid19 working at home among the surveyed organisations stood at an average incidence of 18% and is expected to rise to 37% on average. Employers indicated that 22% of their workforce would continue to work from home post pandemic when compared to 9% before. This is best captioned by Fig 2 below

Projections on Homeworking Post Pandemic

Source: Cipd, 2020

In a different study by McKinsey and Company the post pandemic future is being pegged on adopting a hybrid virtual model that combine working time in the office and remote working. This decision is hinged on the realisation that during the pandemic, working remotely had resulted in solid productivity increases (Alexander et al., 2021). Subsequently, most employees surveyed in the study said that they would prefer a flexible working model post pandemic. Additionally 30% indicated that they would consider switching jobs should the organisations they worked for decide on a fully on site work practices (Alexander et al., 2021) this is a big concern for employers as high turnover rates in a company are not only costly but also diminish employee morale which ultimately reduces their productivity levels. . To further accentuate on employees perspective on working from home above 50% of employees had stated they would like working from home for three or more days per week. This was mostly cited by employees that have young children at home which goes to the growing need for employers to provide a working environment that support employees beyond the workplace measures. In light of this, the pandemic period has proved that working from home is a possibility that does not have to result to loss making organisations rather it has a ripple effect of having employees who are enjoying a work life balance and thus are more productive.

The business case for organisations on homeworking can be justified by the following benefits enhanced work-life balance (61%), increased collaboration (43%), heightened ability to focus with less distractions (38%) as well increased IT upskilling at (33%).other associated benefits but less enhanced include improved health and wellbeing (20%), ability to meet work demands (14%) as well as increased motivation levels (13%) (Cipd, 2020).

In respect to pay and recruitment freeze, the economic uncertainty prevalent during the pandemic led to organisations implementing measures that would help them stay afloat and operational such as freezing pay rise and recruitment. Instead organisations resulted to non-standard work models such as use of contingent workers in a bid to adopt flexible workforce management measures. This is bound to persist post the pandemic as it saves organisations on costs associated with having full time employees such as periodically raising their salaries as well as ensuring that their career progression is catered for whilst integrating it with training and development. Research findings by Gartner indicated that 32% of organisations are already replacing full time employees with contingent workers in a bid to have enhanced workforce management flexibility and thus save on cost (Baker, 2021). Moving forward, there is need to measure the impact of this trend when contrasted to having full time employees. This is cognizant of the fact that employers are always looking to maximise on talent performance whilst attracting the least cost possible. Nonetheless, as the global economy recovers it will be important for people professionals to evaluate the best move. Sreshtha (2020) argued that post pandemic the recruitment function will adopt a mix of both permanent and temporary workers depending on demand-based work or seasonal upsurge. Other aspects of recruitment changes that will persist post pandemic is the use of technology in the recruitment and interviewing process.

Baker (2019) summarised the following changes that will persist post pandemic in reference to organisational work for instance increased data collection. Pre-covid19 organisations were adopting non-conventional employee monitoring tools and this is bound to heighten in the quest to monitor remote workers and in the collection of employee health and safety data. Additionally, the employer is expected to continue having an expanded role in the physical, financial and mental well-being of employees in a bid to promote and improve on employees’ wellbeing and thus have improved organisational performance.

In conclusion, business as usual post pandemic is not realistic as organisations seek to capitalise on some of the measures that were noted to cut operating costs and those that improved on employee productivity such as homeworking. Nonetheless, it is important to also recognise that this not true across all industries for example such as the air travel and hotel industry that significantly suffered during the pandemic. These industries require in person presence for them to function maximally. Knowledge workers on the other hand were presented with an opportunity to test the much sought flexibility and thus moving forward might remain in those companies that allow them to work remotely and only go to the office occasionally. People professionals therefore need to keep tabs with the developments and the competitive needs of the talented workforce so that they are able to attract and retain them. Organisations on the other hand having learnt on the need to be flexible and easily adapt in unprecedented situations are unlikely to sink to the business as usual model.

Bibliography

Alexander, A., De Smet, A., Langstaff, M. and Ravid, D. (2021). What employees are saying about the future of remote work | McKinsey. [online] www.mckinsey.com. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/what-employees-are-saying-about-the-future-of-remote-work.

Baker, M. (2021). 9 Future of Work Trends Post-COVID-19. [online] Gartner. Available at: https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/9-future-of-work-trends-post-covid-19.

CIPD (2020). Embedding new ways of working: implications for the post pandemic workplace. [online] 151 The Broadway London SW19 1JQ United Kingdom: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, pp.1–28. Available at: cipd@cipd.co.uk.

Sreshtha (2020). Re-imagining Recruitment In The Post-pandemic World. [online] Blog. Available at: https://www.talentlyft.com/en/blog/article/394/re-imagining-recruitment-in-the-post-pandemic-world.

SOLUTIONS : TASK 3

In the recent past, flexible working arrangements has been contended in organisational board rooms as well as in research studies in reference to promoting employee wellbeing and offering the much coveted work-life balance. Employers, hold the maximum power in the implementation of the flexible working initiatives and Pre-Covid19 some employers had embraced the concept while others were sceptical terming it as the license to shirk in people management. However, with the imposition of covid19 prevention measures of social and physical distance, regular hand washing and wearing of masks many organisations reacted by giving a forced attempt to the remote working concept. It is during this quest to survive that more employers have experienced first-hand the benefits of flexible working arrangements for their employees. In light of this, there is an argument that employers are the main winners in the move towards implementation of flexible working initiatives. This article will argue that indeed employers are the main winners in this quest.

Flexible working initiatives can be defined as work schedules or work environments that are not bound to the constrains found in conventional work schedules such as working from eight in the morning to five in the evening. Flexible initiatives allow employees to focus on delivery of work with flexibility on how your work day will start and end as well as the work context of the employees which in this case is not confined to the office. (Indeed Editorial Team, 2022).

Prior the emergence of Covid19 flexible working initiatives had been initiated in some companies for example in the US PwC’s remote work survey indicated 29% of financial service companies had 60% of the workforce working from home at least once in a week (Whiting, 2020). Post Covid19 it is expected that 69% of financial companies will have 60% of the workforce working from home at least once a week. In the UK, a study evaluating the impact of remote and flexible working practices noted that pre-pandemic 5% of the workforce had worked from home in 2019 and increased to 46.6% by April 2020. This is expected to increase post pandemic due to the accrued benefits (Hobbs, 2021). This is complemented by a survey of 5000 UK employees where 50% expressed preference for working from home at least two days a week while 30% indicated they could completely work from home five days a week (Cuthbertson and Nitzsche, 2021).

Hearn (2017) argued that the business case for flexible working initiatives for the employers is to realise some of the business benefits associated with the practice. Evidence indicate that flexible working has a financial edge when compared to the conventional working practices. Remote working for example was noted to lead to happier and productive workers when compared to office dwelling employees. In addition, flexible working practices are increased to heightened employee loyalty which in turn translates to reduced employee turnover which saves organisations the cost of constant recruitment, training and development as well as meet client expectations (Hearn, 2017).

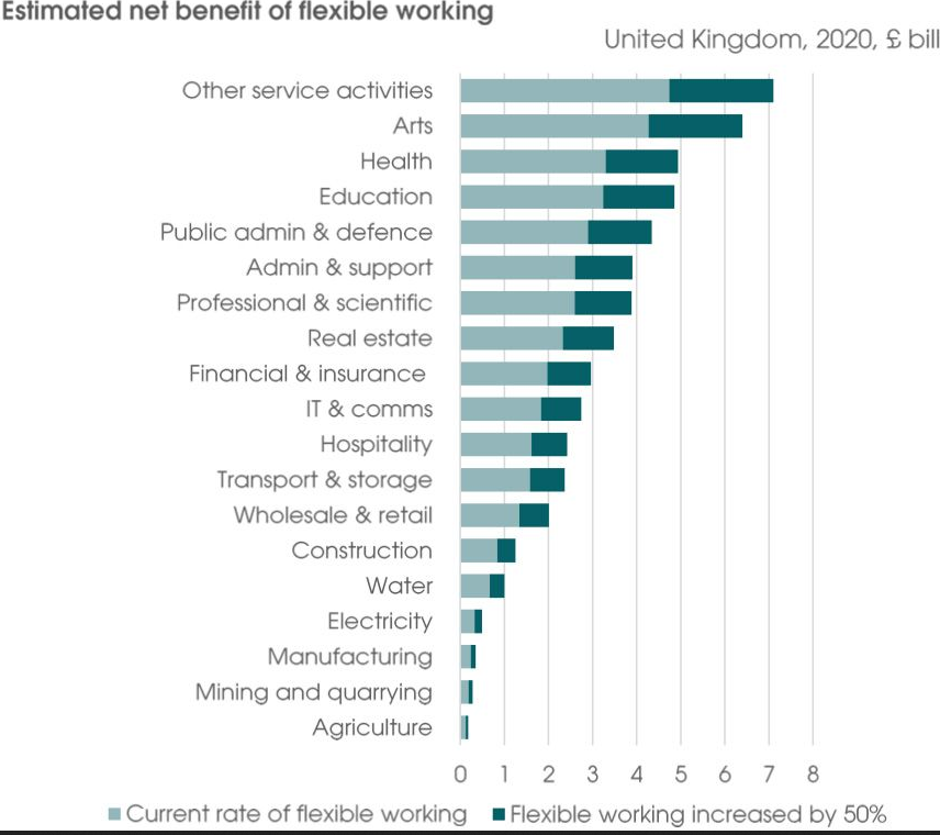

Prior to 2020, research studies and experts have responded to the aspect of overworked employees with the recommendation for adopting flexible working initiatives. This premised from evidence such as the case of the US, where employee stress costs employers over two hundred and fifty billion dollars in lost time alone (Consultancy.uk, 2021). A Cipd study in the UK demonstrated that 20% of workers were stressed due to strained family relationships while 19% were stressed by conflict between home and family life (Half, 2020). The numbers proved there was need to address employee stress in order to boost their productivity levels and thereby improve on organisational performance. According to a research by Pragmatix Advisory flexible working during the pandemic made a significant contribution to the UK economy for example it reduced employee absence as well as heightened productivity by £12.7 billion (Consultancy.uk, 2021). In addition, it reduced hiring and training cost by £2.9 billion which in totality was estimated to contribute £37 billion to the UK economy. These figures are essential to employers as they bear the brunt of high rates of absenteeism and high rates of turn over attributed to employee dissatisfaction. The following is the approximated net benefit of flexible working across various fields in the UK

Source: (Consultancy.uk, 2021)

Flexible working initiatives have also been linked to a competitive edge of attracting top talent. Research findings indicated that 39% of UK employers use flexible working as a benefit in the quest to attract top performing talent. Consequently, flexible working also leads to increased retention of talented employees as they are more satisfied with a flexible work schedule (Half, 2019). To confirm this, Global Workplace Analytics denoted that 95% of employers had recorded improvement in employee retention with the implementation of remote working options (Half, 2019). To this end a 2022 salary guide for business leaders had recognised that 45% of employers had offered flexible working as a standard benefit while 54% were working on enhancing flexibility in their organisations.

In conclusion, the benefits of flexible working to employers can be summarised to increased cost effectiveness and efficiency due to saving made on consumables at the office, diminished absence attributed to sickness and stress, heightened job satisfaction among employees thus reduced turnover, increased employee motivation which lead to better performance as well as ability to attract top performing talent who are otherwise deterred by conventional work models. Ultimately, studies seem to agree that flexible working hours have an added advantage to both employers and employees. Nonetheless, the implementation of flexible working should be considerate of the fact that it is unlikely that there will be increased productivity among all employees due to adoption of flexible working hours. Thus, the need for employers to exploit what will work for the diverse skills set of employees and consider the different types of flexibility that fits within the organisational operations and culture. The net benefits of flexible working hours extends to the global needs for sustainable development goals (SDGs) in respect to aspects such as saving on use of gasoline travelling to work thus climate change as well as access to promote achievement of higher levels of productivity of economies through diversification, innovation and technological upgrading.

Bibliography

Consultancy.uk (2021). Flexible working contributes £37 billion to the UK economy. [online] www.consultancy.uk. Available at: https://www.consultancy.uk/news/29874/flexible-working-contributes-37-billion-to-the-uk-economy.

Cuthbertson, K. and Nitzsche, D. (2021). Who are the winners and losers of flexible working? [online] www.peoplemanagement.co.uk. Available at: https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/article/1746226/who-are-the-winners-and-losers-of-flexible-working.

Half, R. (2019). 5 Benefits of Flexible Working for Your Employees. [online] www.roberthalf.co.uk. Available at: https://www.roberthalf.co.uk/advice/human-resource-management/5-benefits-flexible-working-your-employees.

Hearn, S. (2017). Flexible Working is a Win-Win for Employees and Companies Alike. [online] Helpscout.com. Available at: https://www.helpscout.com/blog/flexible-working/.

Hobbs, A. (2021). The impact of remote and flexible working arrangements. post.parliament.uk. [online] Available at: https://post.parliament.uk/the-impact-of-remote-and-flexible-working-arrangements/.

Indeed Editorial Team (2022). 10 Types of Flexible Working Arrangements. [online] Indeed Career Guide. Available at: https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/flexible-working-arrangements.

SOLUTIONS : TASK 4

Business ethics is a huge concept in the 21st century as companies have become aware that unethical practices can result in huge legal fines as well as dampen the company reputation and instantly become loss making ventures. This is drawn from mega corporate scandals such as Volkswagen’s emission and Enron’s accounting fraud scandals. Business ethics therefore garners interest not only from consumers but also from governments, the fourth estate and regulators. Simply defined, business ethics refer to application of ethical values such as honesty, fairness, integrity and openness in the conduct of a business (Dando & Bradshaw, 2013). From an organisational perspective, the role of inculcating organisational values is a function of the HR through learning and development. Kreissmann and Talaulicar (2020) accurately stated that ethics training and the inculcation of ethics in training programs in organisations is an essential component in the institutionalisation of business ethics. In this regard, ethics training is a constituent of Human Resource Development and plays a significant role in the formation and development of such training therefore making HR the guardian of organisational ethics (Kreissman and Talaulicar, 2020). It is against this background that this article will delve into the role of HR and L&D functions in the achievement of business ethics.

To begin with HR through L&D can help in embedding ethical values through regular internal communication bolstered by occasional training and development. A study by CIPD revealed that communication of ethical values is a constant problem in organisations as only 29% of employees indicated they understood the organisational values of their employer to a great extent (Dando &Bradshaw, 2013). To this end, people professionals should not be content with merely imparting employees with knowledge on business ethics rather they should regular communicate the relevance and significance of high ethical standards in the conduct of all company functions.

Secondly, HR and L&D function can support attainment of business ethics through developing materials that support the employees in their day to day responsibilities. This can include having a set of compliance diktats such as “thou shall not commit fraud” supported by animated clip art sent to all employees’ emails as a reminder as well as issuing employees with a business ethics manual that is regularly updated. This is in cognizance of a study published by the Harvard Business Review that indicated that ethical breaches in companies are not attributed to corruption, bribery or anti-competition rather it is due to extra-legal grey areas such as ignoring cross cultural values after globalisation. Adobe utilises a blog to regularly update employees on expectations on matters ethics and inclusivity to mention but a few (Gillen, 2019). The blog reinforces training and development and serves as a constant reminder to the employees on active company culture and the expected individual ethics among the employees and stakeholders to the company (Gillen, 2019).

Thirdly, it can also be taking a moment after dinner after a long training when a HR or L&D professional takes time to address the audience by giving a good scenario when business ethics saved an organisation or professional from a dire situation (Dando & Bradshaw, 2013). Use of targeted ethical scenarios is an effective training strategy as it links learning and development to real life experiences in the business world. This helps to decipher what aspects of theory is applicable in actual professional practice. It also helps the employees to discuss scenarios that are relevant to the business and thus brainstorm on how to ensure that business ethics are adhered to.

Fourth the HR can make a significant contribution to attainment of business ethics through leading by example and thus modelling the behaviour that is identifiable to the company ethics. For example, they can hire with emphasis being placed on ethical behaviour and regularly communicate the significance of ethics in employee meetings. This can be exemplified by the case of Intel that made a decision to halt sourcing of materials from conflict zones because it was the right thing to do. There were cost implications to the decision but on the other hand it earned positive recognition from consumers as well as other stakeholders. This is agreement to the findings that a reputation of ethics is essential in attracting and retaining consumers as well as employees. Gillen (2019) further asserts that job seekers are attracted to companies that have shared ethical values. In addition, leading by example has a trickledown effect that helps in retaining top talent, develop a culture of ethics and implement sustainable practices (Gillen, 2019). The contrast is also true.

Fifth HR function can support attainment of business ethics through rewarding ethical behaviour in appreciation with the cliché that what gets rewarded gets repeated ( Gillen, 2019). It is important that HR makes it clear that winning at a cost is not tolerated and is ideally more expensive when contrasted to the ethical lapses in companies such as Wells Fargo, Nike and Facebook. In this regard, companies can put an incentive to ethics such as promoting employees that demonstrate ethical behaviour and creating a peers and supervisor nomination system that recognises ethical behaviour (Gillen, 2019). The HR should therefore include work ethics in the criterion for employee rewards and recognition in order to promote adherence of business ethics among the staff. To control the cost of rewards it can be as simple as offering travel perks or offering front row parking to ethical employees (Gillen, 2019).

In conclusion, this article has established that HR and L&D functions can support attainment of business ethics through five major ways including having regular internal communication combined with regular training on business ethics. Secondly by complementing training with business ethics resources and materials such as compliant diktaks and business ethics manuals. It can also proceed through having targeted discussions on ethical scenarios with employees whenever an opportunity presents itself or leading by example and thus serving as a role model in making ethical decisions. Finally, the HR can support through aligning the rewards strategy with ethical behaviour and hence promoting and recognising ethical employees.

Bibliography

Dando, N. and Bradshaw, K. (2013). Rebuilding trust: the role for L&D. [online] Training Journal. Available at: https://www.trainingjournal.com/articles/feature/rebuilding-trust-role-ld.

Gillen, J. (2019). 4 Ways to Foster an Ethical Workplace. [online] www.linkedin.com. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/4-ways-foster-ethical-workplace-james-gillen/?trk=read_related_article-card_title.

Kreismann, D. and Talaulicar, T. (2020). Business Ethics Training in Human Resource Development: A Literature Review. Human Resource Development Review, [online] 20(1), pp.68–125. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1534484320983533 [Accessed 1 Jan. 2021].

NB: You can get a copy of 7CO01 Assignment Answers by visiting cipd level 7 assignment help today.

[vc_row full_width=”” parallax=”” parallax_image=””][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”default”][/vc_column][/vc_row]